Free legal aid is a cornerstone of India’s justice delivery system, rooted in the constitutional vision of ensuring equal access to justice for all, irrespective of financial status or social position. Yet, despite ambitious targets and an elaborate institutional framework under the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987, the reach of legal aid in India remains modest, raising concerns about the system’s effectiveness and sustainability.

The Promise of Legal Aid

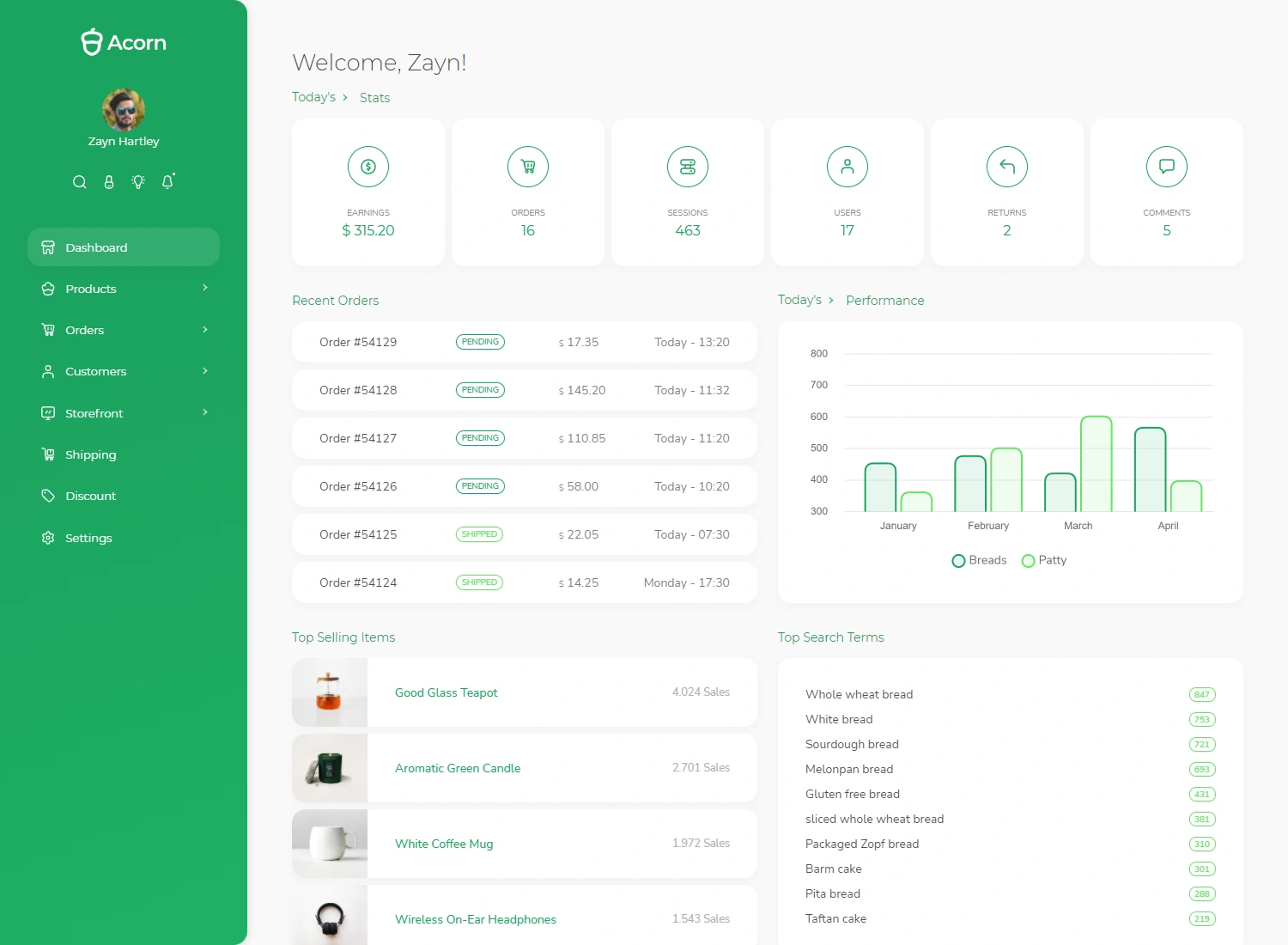

Legal services institutions, operating through the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA), State Legal Services Authorities (SLSAs), and District Legal Services Authorities (DLSAs), are mandated to provide free legal counsel and support to nearly 80% of India’s population. This includes people below the poverty line, marginalized groups, Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, women, children, victims of trafficking, persons in custody, and others covered under Section 12 of the Act.

Between April 2023 and March 2024, just 15.5 lakh people accessed legal aid services — a 28% increase from the previous year but far short of the envisioned scale. For a country with over 1.4 billion people, the gap is glaring.

Front offices attached to local courts, prisons, and juvenile justice boards, along with village-level legal aid clinics, form the backbone of this system. Yet, as the India Justice Report 2025 points out, there is only one legal services clinic for every 163 villages — highlighting the uneven availability of access.

Budgetary Prioritisation and Constraints

One of the foremost challenges is financial. Legal aid accounts for less than 1% of India’s overall justice budget (police, prisons, judiciary, and legal aid combined). Funding comes both from the Centre, via NALSA, and from State budgets.

-

Total allocations rose from ₹601 crore in 2017-18 to ₹1,086 crore in 2022-23.

-

State contributions doubled from ₹394 crore to ₹866 crore, with some States like Karnataka, Maharashtra, and Madhya Pradesh leading with over 100% increases.

-

However, NALSA’s own budget fell from ₹207 crore to ₹169 crore in this period, with utilisation rates dropping from 75% to 59%.

NALSA’s 2023 Manual further restricts spending by SLSAs on hiring staff, vehicles, and certain victim support activities, ring-fencing funds largely for litigation, outreach, and mediation.

Per capita spending reflects uneven prioritisation. The national average stood at ₹6 in 2022-23. Haryana spent ₹16 per capita, while States like West Bengal (₹2), Bihar (₹3), and Uttar Pradesh (₹4) lagged far behind.

Shrinking Frontline Capacity

Perhaps the most visible effect of low fiscal priority is seen in frontline manpower: para-legal volunteers (PLVs). These trained community members spread legal awareness, assist in dispute resolution, and bridge the gap between citizens and institutions.

-

The number of PLVs fell by 38% between 2019 and 2024 — from 5.7 per lakh to just 3.1 per lakh population.

-

In West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh, the figure was as low as one PLV per lakh people.

-

Low and stagnant honorariums compound the problem: while Kerala pays ₹750/day, most States offer ₹500, and a few (Gujarat, Meghalaya, Mizoram) just ₹250 — often less than minimum wages.

This not only deters participation but also reduces the capacity to provide consistent legal aid, especially in remote and vulnerable areas.

Legal Aid Defence Counsel Scheme

In 2022, NALSA launched the Legal Aid Defence Counsel (LADC) Scheme, modelled on the public defender system. Unlike empanelled lawyers who represented both accused and victims, LADCs focus solely on accused persons, ensuring quality defence representation.

-

It now operates in 610 out of 670 districts.

-

In 2022-23, the scheme utilised ₹200 crore fully.

-

However, allocation dropped to ₹147.9 crore in 2024-25, raising concerns about sustainability.

While the scheme holds promise, especially in reducing trial delays and improving quality of representation, it is still in its early stages.

Persistent Gaps

Despite gradual progress, the legal aid system continues to suffer from:

-

Inconsistent service quality: Many empanelled lawyers treat legal aid as a secondary activity.

-

Weak accountability: There is limited monitoring of outcomes and quality of representation.

-

Lack of trust: Many vulnerable citizens still approach private lawyers, fearing stigma or poor quality in free legal aid.

-

Limited coverage: Clinics and PLVs remain inadequate compared to demand.

Why Legal Aid Matters

Access to legal aid is not just about litigation. It is tied to fundamental rights under Article 39A of the Constitution, which directs the State to ensure free legal aid to secure justice for all. Without robust legal aid:

-

Prisoners remain under-trial for years.

-

Marginalised citizens fail to claim entitlements.

-

Women and children face barriers in accessing remedies.

-

Constitutional promises of equality before law remain hollow.

Way Forward

-

Increased Funding: Legal aid allocations must rise substantially, with spending tied to measurable outcomes.

-

Strengthening Frontline Workforce: Revise honorariums for PLVs, expand their coverage, and incentivise their long-term participation.

-

Capacity Building: Regular training and evaluation of empanelled lawyers, coupled with monitoring mechanisms.

-

Public Awareness: Large-scale campaigns to familiarise citizens with their right to free legal aid.

-

Integration with Technology: Use of legal aid apps, helplines, and digital kiosks in villages to bridge awareness and access gaps.

-

Strengthening LADC: Ensure sustained funding and gradual expansion to all districts.